Beyond Corporate Social Responsibility –A Human-Centred Approach to Business Ethics in the 21st Century

Marianthe Stavridou

Head of Business Ethics at Center for Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability (CCRS) at the University of Zurich, Switzerland

Sumon Vangchuay

International human rights lawyer and independent research consultant at CCRS.

Abstract

This article examines the assumptions behind our understanding of ethics in corporate social responsibility (CSR), particularly the meaning of ‘ethical responsibility’ to do what is ‘right’, ‘just’ and ‘fair’. We argue that the presuppositions of human needs, motivation and rationality under the dominant economic paradigm hamper our understanding of ethics in CSR. Using a linguistic perspective, we inquire into the ways in which language, human rationality and normativity can be misinterpreted. We take issue with fundamental assumptions of a neoclassical economic man model. The relentless pursuit of self-interest not only distorts the meaning of laws and ethics but also limits the ideas of social responsibility and disconnects CSR from essential human values. To overcome the constraints of CSR, we propose a shift from compliance and avoidance of violation to integration and embeddedness of human-centred norms and institutions. Properly conceptualised, business human rights responsibility can engender business ethics and better equip companies to deal with the social and economic anxieties of the 21st century.

Keywords: business & economics; business ethics; corporate social responsibility; language; human rights

Please note that:

- words in italics are lexical entries

- words in “” are citations

- word in ‘’ are referring to meanings / semantic fields

-----------------------

“Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do.”

-Potter Stewart, Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (1958 – 1981)

-----------------------

Introduction:

The Crucial Role of Business Ethics in the 21st Century

As the corporate world still searches for its moral conscience, a plethora of breakthroughs and challenges occurs alongside an unprecedented level of socio-economic anxieties across the globe [[1]]. Leaders are pulling resources to harness emerging technology while struggling to deal with the impact of its disruptions on social and economic institutions. As the founder of the World Economic Forum puts it, we are experiencing “nothing less than a transformation of humankind”. Not only are we forced to enter the “beginning of a revolution that is fundamentally changing the way we live, work, and relate to one another” [[2]]. The mounting dilemmas and anxieties in the age of the unknown have also made us confront “who we are”, individually and collectively [[3]].

While much has been discussed about the need for business to capitalise on new technology, much less attention is paid to the rationality and assumptions behind corporate social performance in the age of anxiety. Lesser consideration is given to what constitutes an ‘ethical responsibility’ for companies to do what is right, just and fair, at the social and human levels. This is worrisome given the weak track record of corporate social performance (CSP) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in addressing the negative effects of business activities on the external environment, such as natural resources, raw materials, employment and distribution of wealth [[4]]. In many circumstances, businesses are seen as widening income inequalities and even turning social problems into economic opportunity [[5]].

We believe that the ability of companies to meet societal expectations lies in their paradigmatic understanding of business ethics. To elaborate this point, we submit two questions: 1) what are the assumptions behind the ethical responsibility to do what is ‘right’, ‘just’ and ‘fair’ in CSR? and, 2) to what extent does CSR embody a positive and constructive notion of human needs and capacity and embed in the social norms and institutions which represent collective human values?

Our main hypothesis is that businesses can meet the human and societal challenges of the 21st century if they align their objectives and strategies with human-centred values, as opposed to purely making profits and complying with legal regulations. We attempt to answer the above questions by inquiring into the prevailing assumptions of ethical responsibility and rationality drawn from the mainstream thinking in business and economics.

Our two positions will be elaborated in this article:

- Ethical responsibility in CSR requires the embeddedness of human-centred values, not legal compliance or avoidance of violation.

- Business human rights responsibility provides a new paradigm that can transform companies into effective social enterprises better equipped to deal with societal challenges.

1. Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility: Rationality and Assumptions

Although defining business ethics is as difficult as “nailing Jello to a wall” [[6]], there are different ways in which one can approach ethics in the context of business. As a recent discipline, business ethics has multidisciplinary contributions from various branches of social sciences, such as moral development, behavioural psychology, organisational theory, business and economics, among others [[7]]. Contemporary business ethics is known less for finding moral principles of what is right and good and more for addressing ethics management and organisational theory. Institutionalised concepts, such as corporate responsibility, sustainability and governance, have largely represented corporate efforts to improve business social performance through crisis management tools. As ethical issues are often seen as peculiar scenarios or on a case-by-case basis, there is a considerable confusion over how companies’ social responsibilities are interpreted due to underlying value-judgements and ideologies [[8]]. Despite the existence of national policy frameworks on CSR, many companies remain reluctant to integrate the concept into their core strategy and operations.

We look at Carroll’s influential pyramid of corporate social responsibility that became the basis for modern definitions of CSR [[9]].

Figure 1. Carroll’s “Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility”

Source: Carroll (1979, 1991).

In this pyramid, corporate social responsibilities are conceptualised into four types. The first and most fundamental type at the bottom of the pyramid is the ‘economic responsibility.’ A company has to be profitable to ensure its survival. The second type is the ‘legal responsibility’ of a company to abide by the laws and regulations of the respective country. According to Carroll, this can be construed as partially fulfilling a social contract [[10]]. The third type is linked to the moral standards not formalised through laws, that is, the ‘ethical responsibility’ to do what is right, just and fair, even when companies are not legally required to do so. Lastly, companies have ‘discretionary responsibility’ to contribute to various kinds of social, educational, recreational or cultural purposes – that which are not economically, legally or morally required [[11]].

It is clear that companies are instructed to consider primarily the first two forms of responsibilities depicted as the base of the pyramid, namely making profits and complying with the law. Although Carroll admitted that society expects companies to behave over and above legal requirements, the concept of corporate ethical responsibility remains “ill-defined” and became the most difficult topic to discuss in the business world [[12]]. It is to no surprise that CSR is seen as a corporate “strategy of being seen to be ethical” – akin to having no ethics at all [[13]].

The premise of corporate responsibility as reflected above does not sufficiently deal with the normative components of economic ethics and, as a result, prevents the ethical dimension of CSR from developing. This is because business ethics and institutionalised concepts such as CSR, despite multidisciplinary contributions, still rely heavily on the mainstream rational theory of economics. Many companies subscribe to the neoclassical ‘value-free’ understanding of the economy and the absence of any ethical and moral precondition in doing businesses [[14]]. While CSR, by its definition, should be connected with human and social values, the priorities in most companies are tied to effective use and control over resources, competitiveness and profits. As moral considerations are less relevant, social and environmental costs can often be justified under business objectives. This raises serious concerns over how any formulation of ‘social responsibility’ can ever be meaningfully asked of businesses.

We feel compelled to raise some very basic yet fundamental questions related to how we consider something to be ethical, right and responsible in today’s business practices.

1.1 What is ‘Right’ and ‘Responsible’? A Linguistic Perspective

The central question in ethics is essentially the question of the right conduct. When we speak of ‘ethical responsibility’, we often apply the notion of what is right without questioning how it has come to dictate our understanding of CSR and business ethics. A linguistic approach can remind us that words carry meanings by relating a sign form to their meaning and shaping their content through social and historical conventions [[15]]. Lexical entries such as right and responsibility are “collective products of social interaction, essential instruments through which human beings constitute and articulate their world” [[16]].

It is helpful to understand the development and evolved meaning of ‘right’ as a lexical entry in Indo-European languages [[17]]. The notion of ‘right’ presents a polysemic development carrying multiple meanings. Its origin in English can be traced back to the early 12th century Old English riht, which means ‘good, proper, fitting, straight’, from the semantic field of *h₃reǵ- [[18]] meaning ‘straight’ and denoting ‘to direct in a straight line’, thus ‘to lead’, ‘to rule’ and, in a legal sense, ‘to establish by decision’ and ‘to rule by law’. The basic notion comes out of the perception of the right hand as the ‘correct’ hand [[19]] because of its property of being the physically dominant hand [[20]], hence ‘strong’ and ‘correct’; the left hand usually being the weaker hand [[21]] takes its origin in the forms of Old English *lyft ‘weak, foolish’, found also in lyft-adl ‘lameness, paralysis’ [[22]]. In the Middle Ages the use of right created semantic variations and patterns that amplified its original denotation as an influence of its Germanic origin. The latest development of right as opposition to left in politics is a loanword from French La gauche first recorded in English in 1837 in reference to the French Revolution and the 1789 seating of the French National Assembly in which the nobility took the seat on the President’s right.

The figurative ‘right hand’ was even more elevated in the Christian usage [[23]]: the right hand of God (Dextera Domini) is Jesus Christ’s honoured placement in heaven accentuating the divine ‘omnipotence’ in the Bible [[24]] and the highest authority of morality in Christian work ethics [[25]].

The lexical entry responsibility, as a noun, means ‘ability to respond’, the ‘condition of being responsible’, ‘that for which one is responsible’ or ‘answerable’ and can be compared also with entries in other Indo-European languages i.e. German Verantwortung. Responsible, means ‘accountable in one’s actions’, ‘reliable, trustworthy’ and approximates the sense of ‘obligation,’ which includes ‘legal obligation’ and over time to be responsible has come to signify ‘answerable to another, for something’. The notion of responsibility has approximated the ‘obligation to be just in front of a supreme instance, to give answers and to ask forgiveness.’ This came from the Greek and Latin origin that implies the relation to divine judgment [[26]].

Linguistic accounts of right and responsibility demonstrate that both terms have come to signify ‘good’ and ‘just’ and carry meanings closely intertwined with law and regulation and the ability to ‘respond to the legal systems’. Throughout history under the force of natural and moral law, the concepts of ‘right’, ‘responsibility’, ‘law’ and ‘justice’ have come often to legitimise the divine-like power of a ‘king’ or ‘rightful ruler’ to rule people by way of ‘regulation, law and justice’ [[27]]. These concepts often appear at first glance to be self-evident, either natural (i.e. natural givens of human life), authoritative and real (i.e., a king) or moral and metaphysical (i.e., a god). For example, the law is considered a priori ethical and just when a god or a king gives the law to common people.

In addition to the bias towards law compliance, an understanding of ‘ethical responsibility’ in CSR is further affected by the use of binary oppositions and semantic contradictions. Oppositions of two seemingly mutually exclusive terms like right and wrong, ethical and unethical or good and evil can be organisers of human philosophy, culture and language [[28]] and be used to frame and limit realities but also create biases. For example, if compliance with the law is legal and ‘legal’ includes ‘ethical’, law adversity or defiance is therefore not only illegal but also unethical. Based on this pattern, we observe the following assumptions:

- compliance is right; defiance is wrong

- compliance is legal; defiance is illegal

- compliance is ethical; defiance is unethical

- compliance is just; defiance is unjust

- compliance is fair; defiance is unfair

- compliance is good; defiance is evil

- compliance is responsible; defiance is irresponsible and so on

The above binary logical pattern of ‘right’, ‘just’, ‘fair’, ‘legal’, ‘good’ and ‘responsible’ points to the same connotation that laws and regulations should be morally positive. Adherence to the law by companies is therefore considered sufficient to fulfil a social contract while their corresponding social obligations are left vague and discretionary [[29]]. Such biases are amplified and reinforced by corporate communications and marketing strategies in order to appeal to the wider public, maximise sales and avoid negative impact on their business and branding [[30]]. Preoccupation with compliance can lead companies to make false judgements and overlook certain social and environmental issues which have been obscured by the nature of laws and regulations [[31]].

When ‘ethical responsibility’ is conflated with ‘legal responsibility’ in CSR, we arrive at contradictions and questionable morality. This is because legal systems and laws can appear, on the surface, to be just and fair, while perpetuating the status quo and substantive inequalities. In theory, law derives its legitimacy from complex normativity and authority which should evolve over time to reflect the changing values of society. However, in many circumstances, unjust laws can be difficult to change because of the powers that sustain them. In a democratic society, substantive inequalities can be challenged by procedural laws and check-and-balance mechanisms. However, in this same democratic society, individuals and groups are also invited to participate in the legislative process to advance their particular interests. Businesses will lobby for passing the law that supports their particular interests. Business ethics are only validated by corporations when they are supported internally by a well-implemented internal compliance programme.

We argue below that the ambiguities inherent in business ethics are a result of the long-standing aversion to morality in the dominant theory of economics [[32]]. Unlike the societal moral construct in a social contract which is determined by society as a collective, CSR is created as a “construct of moral responsibilities” for society while its content is determined by corporations [[33]]. This runs counter to the premise of a social contract [[34]]. If businesses are genuinely conceptualised as part and parcel of a society, the society can reasonably expect businesses to not only advance their interests in a manner that is not detrimental to its social fabric and welfare, but also contribute to the environment and the communities involved [[35]].

1.2 Assumptions of Human Rationality in Business

The commonly held framework of corporate social responsibilities (economic, legal, ethical and discretionary) is subjected to the paradigm of an economic man who is presumed to be primarily rational and self-interested [[36]]. When appropriated by neo-classical economists, an economic man extends his focus on maximising wealth to maximising utility, that is, connecting efficient means with wealth described as benefits for the individual [[37]]. By extension, his economic reasoning is considered a neutral process and “the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses [[38]]”. Economics became a system of thinking which is only concerned with what is, rather than what ought to be.

This deductive methodology took a narrow view of human needs and motivation and built a simplified grand scheme of the economy that primarily serves two types of actors. On the one hand, businesses are assumed to maximise their profits from producing and selling goods and services. On the other, individuals and their households are assumed to maximise their utility or satisfaction from consuming goods and services. These two different economic agents are supposed to interact in perfectly competitive markets. Within this paradigm, only the social and economic agents and institutions that uphold this rationality can optimise self-interest and presumably create maximum benefits and welfare for society [[39]]. The entire system is deduced from one essential axiom: “rational economic man maximizes his utility” [[40]].

Such a narrow view of human nature and lack of contextual awareness are largely criticised for contributing to today’s most serious structural problems. Neoclassical economists almost uniformly failed to detect the growth of the financial and real estate bubbles, the dramatic increase of income and wealth inequalities and an ever-greater concentration of economic and political powers in ever-larger corporations [[41]]. Much has been written on how a relentless pursuit of self-interest is fundamentally at odds with the development of human societies and is destined to lead human species towards the “tragedies of the commons” [[42]].

CSR is set up for failure in a paradigm where economics is believed to be value-free and devoid of normative values [[43]]. As we have seen, the inability of modern economic institutions to connect with human needs and motivation beyond production and optimisation has led to widespread disenfranchisement, fear and anxieties [[44]]. According to Illich, modern institutions created to uphold the rationality of an economic man contradict social ends and erode the dignity and competence of peoples and communities who were perfectly capable of trading in a friendly and lively way [[45]]. Without human and social connections, business-related advertising activities increasingly reduce people to a category of incompetent consumers, lacking the ability to satisfy their well-being and livelihoods. While business transactions continue to produce unintended consequences for communities affecting every aspect of social life [[46]], the idea of ethical business responsibility, if such exists, is more responsive to the needs of shareholders than to the spirit and moral questions of society.

A powerful theory on human rationality and human-centred values is needed to contest the premise of the economic man paradigm. From a linguistic perspective, the generative principles of the human brain, as advanced by Noam Chomsky, see the structural mechanisms of the human brain and our language acquisition as corresponding to rationalist principles [[47]]. In contrast to the neoclassical economic notion of human motivation, his theory of the human capacity in language builds on a classic liberal tradition of Humboldt, which sees human natural capacity as “self-perfecting, enquiring and creative” [[48]]. Understanding the generative structure of the human brain in relation to language can shed light onto how humans have evolved with the ability to create social conditions and forms to maximise the possibilities for freedom, diversity and individual self-realisation.

Freedom, according to Chomsky, is the condition under which the human brain limits and applies constraints to understand language and other things by following specific rules [[49]]. In this sense, the inner form of language (the rules) is the mode of denoting the relations between the parts of the sentence and it reflects the way people regard the world around them. The human brain has these innate rules that allow it to conjure up the world where human beings are able to survive and be free within its natural limits. However, the human brain has its limits of understanding in the same way that the human body grows and develops within the limits of its nature. Human freedom is therefore subject to limits because the human brain uses specific rules making an “infinite use of finite means” to create an understanding of the world [[50]]. This rational capacity is limited by the set of attributes, the rules, that the human brain applies in its development [[51]]. For example, the human comprehension of the economy is essentially developed and limited by the constraints regarding this understanding [[52]].

Chomsky connects his theory of human language capacity and rationality for free thought and self-expression to the classical liberalism of Rousseau. Rousseau viewed the human consciousness of freedom and the ability to strive for self-perfection as unique to the human species because they distinguish us from the “beast-machine” [[53]]. To Chomsky, the same human capacity for creating language and assigning forms is also used to maximise the possibilities of human freedom, diversity and individual self-realisation. The condition of freedom is a prerequisite for deriving motivation and pleasure from any creative and self-fulfilling undertakings in our social life.

2. Business Ethics in the ‘Human’ and ‘Social’ Paradigm

Chomsky’s rationality of freedom provides a humanist counter-narrative to that of the economic man, which rewards the exploitation of others and which is, by definition, “anti-human” [[54]]. To be more attuned to human values, companies have to go beyond the CSR paradigm of profits and compliance and appeal to the personal and human agency of stakeholders. Companies can be part of a rational social order which adopts an optimistic and protective approach to the human capability to envision and create a meaningful and productive life for everyone. A deliberate choice by companies, as opposed to a vague and discretionary one, to align their business objectives and strategies with human-centred values such as freedom and dignity should be taken seriously by business ethicists.

Although freedom carries an intrinsic value for an individual and is fundamentally personal, the concrete benefits of personal freedom can only be manifested and amplified at a collective level. This means that individual freedoms can be realised in the form of personal interdependence [[55]] and that members of a community can increase their individual freedoms by enlarging their community’s freedom [[56]]. If there is a social contract regulating the relationship between individuals, society and government, a corporation as a natural person and member of society should be part of that relationship. The theory of political social contract should have bearing on the social responsibilities of corporations [[57]].

But how can businesses justify their alignment with commonly held human values such as the respect for the dignity and freedom of others?

2.1 Social Embeddedness

The idea of social embeddedness can be used to contrast the idea of an atomised economic rationality and to better align organisational decisions with social action and institutions. Granovetter proposes an approach of embeddedness which neither reduces social actions and behaviour of social choice to abstract optimising rationality (formalist) nor subjugates social relations and actions to over-socialised conceptions or a fixed set of monolithic normative principles (substantivist) [[58]]. An ‘embedded’ individual will have their choices and actions conditioned by ongoing actions and expectations of others [[59]]. For Granovetter, a social choice is interpersonal and relational and is conditioned through the idea of trust, thus making up a social reality within a system of economic actors. Based on trust, actors choose to act, whether good or bad, on the basis of expected cooperation from other actors. According to Granovetter, it is possible to have an embeddedness approach which underlines the role of concrete personal relations and structures or “networks” of relations and how trust plays a role in confirming or dismissing certain normative choices [[60]].

Granovetter’s idea of relational embeddedness can help companies probe their ethical parameters through an understanding of how a social choice can be made deliberate to promote human values. If individuals choose how to act based on cooperative consideration of the likely action of others, concrete social relations will become critical to individual actions. Importantly, when actors react and respond to ongoing social relations, their actions are also constructed through their convictions, consciousness and purposes. If purposive social actions can be embedded through concrete and ongoing systems of social relations, social connections can affect purposive action and challenge previous results that occurred in an atomist rationalist paradigm [[61]]. His critique leads us to reconsider social norms and institutions in light of social actors’ convictions, consciousness and purposes [[62]].

Importantly, to move businesses towards a human-centred social order, an alternative paradigm of socially embedded corporate responsibility is required. Below we look at another powerful alternative narrative of ‘business and human rights’ where markets are believed to work optimally only if they are “embedded within [social] rules, customs and institutions” [[63]]. Grounded firmly in the theory of business and society, this approach sees companies as requiring social rules and institutions in order to thrive and successfully manage the adverse effects of market dynamics and to provide the public goods that markets undersupply. Under this new paradigm, businesses “must learn to do many things differently” [[64]] under some structure of conviction, consciousness and purpose.

2.2 From CSR to Human Rights

It is no coincidence that the principles of social contract are central to the organisation of the international human rights regime, where the concepts of freedom and equality are powerful forces [[65]]. Human rights have been understood as the “flip side” of duties under a social contract [[66]]. Their natural and universal basis has already been firmly established as norms and institutions indispensable for international peace and security [[67]]. These norms and institutions, which states have committed to apply for everyone, can serve as an authoritative catalyst for companies to connect corporate responsibilities to human-centred social values.

As corporations have taken a form of global institution, business leaders are increasingly expected to elaborate on their role in the protection of human rights. International human rights obligations require states to not only uphold democratic institutions and advance certain liberal values but also involve businesses in the consensus-seeking process on human rights. With mounting criticisms against transnational corporations and the effects of business activities on communities, businesses have incentives to engage. Both sides of the CSR and human rights debates agreed at the very least on the need to move beyond the old CSR to a new, more meaningful platform and action on business and human rights [[68]].

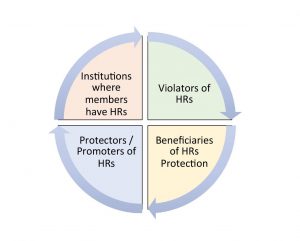

According to Bottomley [[69]], the relations between corporations and human rights can be approached in four distinct but interrelated dimensions:

Figure 2. Corporations and Human Rights: Bottomley’s Four-dimensional Relationship Matrix

Source: Bottomley, 2002.

This matrix offers a good starting point for exploring possible ways corporations can be related to human rights norms and institutions. While they are often thought of as violators of human rights, corporations and their employees are also beneficiaries of human rights under national or international laws. They may also be the subjects of the protection of human rights in a human rights agreement. This dynamic relationship is supported by CSR literature which highlights a global CSR trend towards human rights-enhancing developments in the 21st century [[70]]. Important developments include the incorporation of human rights measures in transnational and international trade and investment, the shaping of various UN norms and guiding principles on business conduct and the creation of tools for incorporating human rights issues in corporate operations, reporting, supply chains and due diligence [[71]].

While there remains general support for integrating a voluntary code of conduct with strong human rights dimensions into corporate structure and cultures, a new agenda of corporate human rights responsibilities is different. Propelled by the works of John Ruggie leading to the adoption of UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) [[72]], the ‘business and human rights’ paradigm is a departure from the old approach to corporate responsibility. Vague and discretionary concepts, which lack specificity and were a source of confusion in CSR such as corporate ‘sphere of influence’, were clearly rejected [[73]]. Ruggie’s deliberate approach to corporate responsibilities is significant because, for the first time, there exist coherent underlying principles of human rights responsibilities which can be concretely assigned to states and corporations based on their respective societal roles.

The UNGP provides important guidelines for companies to prevent human rights abuses and address human rights concerns in their business operations. It covers all business enterprises, regardless of size, industry or location. Companies are asked to identify and assess negative human rights issues and ensure that their policies are adequate to address them [[74]]. In order to prevent and mitigate abuses, companies must not only know their actual or potential adverse impacts but also demonstrate how they respect human rights in all their operations.

One important benefit for aligning corporate responsibility with human rights is the protection of children and vulnerable groups and the communities affected by business activities [[75]]. Due diligence requires companies to identify and address the human rights impacts across their operations and related products through their suppliers and networks. Wherever possible, they should also engage with the communities or groups potentially affected by their operations [[76]]. In conflict-affected areas where gross human rights abuses are often connected to business enterprises [[77]], states also have obligations to put in place assistance and enforcement mechanisms to ensure that businesses are not engaged in such abuses in conflict-affected areas. The due diligence approach reinforces the existing international human rights obligations which protect minorities, indigenous groups and vulnerable non-citizens such as asylum seekers, migrants, refugees and displaced persons who are prone to human rights abuses by businesses.

2.3 Beyond CSR: Business Human Rights Responsibility

As aptly put by Ruggie, “[e]mbedding the corporate responsibility to respect human rights is about making respect for human rights part of the company’s DNA [[78]]”. In the figure below, we outline possible transitional concepts and tools which businesses can use to move beyond CSR and frame their corporate responsibilities for human rights.

Figure 3. Moving Beyond CSR: Towards Human Rights Responsibilities of Businesses

To move beyond the old paradigm of CSR, companies must adapt their leadership and operational capacity to effectively respond to unforeseen circumstances in ways that respect the human rights of all stakeholders to the greatest extent possible. To fulfil the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, companies are required to be accountable in three ways [[79]]. First, companies should have a clear public statement on their policy commitment to respect human rights that is also reflected in companies’ core structure of values, philosophy, principles of conduct and key performance indicators, among others [[80]]. To this end, leadership from the highest levels plays a critical role in embedding the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, internally and externally. On the one hand, effective leadership can transform a high-level policy statement into company-wide commitment and robust operationalisation plans. On the other hand, a company’s leadership can signal the paradigmatic shift in its value creation and proposition to other stakeholders. The authenticity of leadership commitment to human rights can be observed and validated, for example, through how often CEOs speak about human rights issues in their speeches; whether CEOs report on human rights issues to their boards of directors and investors; how CEOs invest organisational resources; or how the performance of employees and suppliers are measured and rewarded [[81]].

Second, companies must employ specific human rights activities, such as human rights due diligence processes, as the principal means of satisfying corporate responsibility to respect human rights. There are different ways in which companies can set up a human rights function to ensure the implementation of human rights activities. Companies can assign an existing function or department, such as legal, human resources, procurement, CSR/sustainability, compliance or community relations, to take the lead. Alternatively, companies can also establish cross-functional working groups involving multiple departments [[82]]. What is important is that specific human rights activities such as due diligence be owned by the operational business units and departments, rather than being conducted from the top down in order to ensure ownership of issues and measures. This is particularly crucial where a corporation has geographically dispersed operations.

Third, companies must have processes in place to enable access to effective remedy for victims of any adverse impacts they cause or contribute to. Grievance mechanisms can include a recourse to government labour relations bodies or national human rights institutions when a private, local mechanism is unable to provide resolution [[83]]. Importantly, companies can use the implementation of grievance mechanisms as “an entry point for internal conversations” about the relevance of human rights. Human rights concerns can be integrated into ‘the language of business’ through references to transparency, early warning systems, risk management and efficiency [[84]].

The approach to corporate responsibilities on human rights under UNGP features a balance between hard and soft law, combining mandatory with voluntary measures and industry and company self-regulation. Its normative reach is extensive; the responsibility to respect human rights by businesses applies to all internationally recognised human rights in the International Bill of Human Rights [[85]] and the International Labour Organization Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work [[86]]. It represents a more specific and deliberate global agenda on business and human rights which demands state responsibility to hold businesses accountable, on the one hand, while requiring businesses to improve in the area of self-regulations, on the other.

Conclusions: A New Paradigm of Corporate Responsibility

Using a linguistic perspective, we found some inherent theoretical and conceptual constraints which hamper the notion of social and ethical responsibility in CSR. First, the focus of ethics in CSR has been eclipsed by the economic responsibility to be profitable and suffered from the conflation between ‘ethical’ and ‘legal’ responsibilities, on the one hand, and between ‘ethical’ and ‘discretionary/philanthropic’ responsibilities, on the other. Second, the relentless pursuit of self-interest not only distorts the meaning of laws and ethics but also limits the ideas of social responsibility and disconnects CSR from essential human values. Third, CSR is a construct of moral responsibilities by corporations instead of society. As a result, the unclear focus of ‘ethical responsibility’ becomes about crisis management, not contributing to or advancing the values of society. Fourth, this is due to the assumptions of human rationality within the prevailing paradigm of self-interest and competitive economic man, which are incomplete, largely misinformed and essentially anti-human.

We propose a fundamental shift in the narrative in order for business ethics to move beyond CSR and be connected with human-centred values such as human rights. To this end, we view the agenda of ‘human rights responsibility’ as providing a powerful and legitimate new paradigm of corporate responsibility. Businesses can strive to advance human intellectual development, grow moral consciousness and mutual respect, highlight cultural achievements and encourage public participation. When business ethics is connected to commonly held collective values, companies will benefit not only in terms of ideas and innovation but also in terms of stakeholder relationships and public image. Respect for the dignity and freedom of others is essential for shaping ethical conduct and preventing malpractices. This requires a deliberate choice by companies to be humanistic and accountable to embed themselves with human-centred norms and institutions. It is an essential step forward for companies to move beyond the conceptual constraints of CSR.

Notwithstanding the progress on setting standards for business and human rights, the challenges in moving beyond CSR remain at all levels. At the level of international law, tensions continue to persist between state and non-state responsibility for human rights. On a practical level, tensions will also persist around the justification and operationalisation of human rights corporate responsibilities because the rationality and approach of human rights will be at odds with some unique characteristics of business such as profit maximisation, resource optimisation and dependency. A traditional approach to business does not favour extra regulations, transparency, disclosure of corporate information, access to remedy and grievance mechanisms and cooperation for official investigation, which are normally required in human rights investigation, documentation and reporting. A clear link between corporate responsibility, human rights and business ethics must be developed at the organisational level. An overall strategy of CSR with a holistic understanding of how compliance and ethics interact within business organisations is crucial.

The promise of corporate human rights responsibilities will ultimately rely on the commitment at the level of organisational decision-making. Business leaders can navigate appropriate social roles and move beyond ethics management to align more closely with the values of their stakeholders. Managers are required to adapt their strategies and objectives in order to make informed judgments at all operational and organisational levels. At the level of personal ethics, human rights concepts (such as freedom, dignity, equality, justice and fairness) can serve as decision criteria for what is right, wrong, fair and just in business practice. The bottom line is: ethical decisions in business cannot be divorced from considerations of what it means to be a human and social being.

Footnotes

[1] Nearly 10% of the world’s population is suffering from depression and/or anxiety. Between 1990 and 2013, the number of people suffering from depression and/or anxiety increased by nearly 50%, from 416 million to 615 million. Mental disorders account for 30% of the global non-fatal disease burden. WHO and World Bank, (2016). Investing in treatment for depression and anxiety leads to fourfold return, joint news release: 13 April 2016, available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2016/depression-anxiety-treatment/en/, accessed 20.10. 2017.

[2] Schwab, K., (2017). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Penguin UK, p. 1. Serious operational and policy discussions among leaders across public and private institutions have already taken shape. e.g. World Economic Forum Annual Meeting: Fourth Industrial Revolution (Davos, 2017): https://www.weforum.org/events/world-economic-forum-annual-meeting-2017.

[3] Schwab, K., (2017), p. 3. See e.g. Bauman, Z. (2013). Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge, Polity.

[4] For an assessment of CSP in the past 50 years, see Stachowicz-Stanusch, A. (2016). Corporate Social Performance: Reflecting on the Past and Investing in the Future. Information Age Publishing. Charlotte, NC. See also Stachowicz-Stanusch, A., Mangia, G., Caldarelli, A. and Amann, W. (2017). Organizational Social Irresponsibility: Tools and Theoretical Insights. Information Age Publishing. Charlotte, NC. See also Stachowicz-Stanusch, A., Amann, W. and Mangia, G. (2017). Corporate Social Irresponsibility: Individual Behaviors and Organizational Practices. Information Age Publishing. Charlotte, NC.

[5] e.g., San Jose Mercury News, (2017). ‘Poverty rates near record levels in Bay Area despite hot economy’, 1 April 2017, available at http://www.mercurynews.com/business/ci_27830698/poverty-rates-near-record-levels-bay-area-despite, accessed on 20.10.2017. Hetherington, J.A.C. (1973). Corporate Social Responsibility Audit: A Management Tool for Survival. London, The Foundation for Business Responsibilities, p. 37.

[6] Lewis, V.P. (1985). Defining ‘Business Ethics’: Like Nailing Jello to a Wall. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 4, No. 5 (Oct), pp. 377–383. Out of 254 texts, Lewis found 308 concepts in the definitions of business ethics.

[7] Business ethics became an established field in 1929 when Wallace B. Donham claimed to “start business ethics as a subdivision of general ethics”. Donham, W.B. (1929), ‘Business Ethics – A General Survey’, Harvard Business Review 7(4):385–94. The development of today’s business ethics can be divided into five main phases: 1) “Ethics in business” (before 1960); 2) “Social issues in business” (1960s); 3) “Emergence, definition, development” (1970s and 1980s); 4) “Ethical decision making and behaviour” (1990s); and 5) Maturity and application (2000s). Exceeding its purely philosophical roots, business ethics in the latter phase has come to concern itself with the application of developed concepts and assessment of ethics management tools for practice. Laasch, O. and Conaway, R.N. (2014). Principles of Responsible Management: Global Sustainability, Responsibility, and Ethics. Cengage Learning, pp. 114–6.

[8] e.g. Visser, W. and Tolhurst, N. (2010). The World Guide to CSR: A Country-by-Country Analysis of Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility. Routledge; Horrigan, B. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility in the 21st Century: Debates, Models and Practices Across Government, Law and Business. Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 39; Kristoffersen, I., Gerrans, P. and Clark-Murphy, M. (2005). The Corporate Social Responsibility and the Theory of the Firm. School of Accounting, Finance, and Economics. FIMARC Working Paper Series No. 0505, Edith Cowan University, p. 2.

[9] e.g. Moon, J. (2014). Corporate Social Responsibility: A Very Short Introduction. OUP, Oxford, Chapter 2. But in his review of CSR literature, Carroll cites Bowen’s work as the basis for modern definitions of CSR. See in Carroll, A.B. (1979). ‘A three-dimensional model of corporate social performance,’ Academy of Management Review, 4 pp. 497–505. Citing Bowen, H.R. (1953). Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. New York, Harper & Row: xi.

[10] Carroll, A.B. (1979), p. 500.

[11] Carroll, A.B. (1979), p. 500. See also Carroll, A.B. (1991). “The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders”. Business Horizons, 34: 39–48.

[12] Carroll, A.B. (1979), p. 500.

[13] Aasland, D.G. (2004). ‘On the Ethics Behind “Business Ethics”, in: Journal of Business Ethics, August, Volume 53, Issue 1, p. 3; Roberts, J. (2001). ‘Corporate Governance and the Ethics of Narcissus’. Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 1, Jan: 2001, pp. 109–127.

[14] Laasch, O. and Conaway, R.N. (2014), p. 118.

[15] Structuralism in sociology and linguistics is the school of thought that sees elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a larger, overarching system or structure. It is used to uncover the structures that underlie the assumptions and biases of what we do, think, say, perceive and feel. Not all meanings in a language are, however, represented by words. For example, in the Indo-European languages, semantic concepts are embedded in the morphology or syntax in morpho-syntactic forms of grammatical categories. The relationship between form and meaning is arbitrary.

[16] Harris, R. (1988) Language, Saussure and Wittgenstein: How to Play Games with Words. London, Routledge, p. ix.

[17] We focus on Indo-European languages, especially English, because they have been key in the development of classical and neoclassical economic models and advanced the idea of globalised market economy.

[18] Right: ‘morally correct’ derives from the Old English riht ‘just, good, fair, proper, fitting, straight, not bent, direct, erect’. This derives from the Proto-Germanic *rekhtaz (source also of lexical entries in Old Frisian, Old Saxon, Middle Dutch and Dutch, Old High German, German, Old Norse, Gothic) which takes origin from the Indo-European root *h3reǵ-, which constitutes one of the two roots for many Indo-European languages including Greek and Latin. The second root is *deks-. [Online Etymology Dictionary], accessed 26.7.2017, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=right.

[19] The usual Old English word for this was swiþra, literally ‘stronger’. Similar notional evolution exists in Dutch recht, German Recht ‘right (not left)’ from Old High German reht, which meant only ‘straight, just’. Compare Latin rectus ‘straight; right’, also from the same PIE root. Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed 26.7.2017, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=left

[20] Up to 90% of the human population is estimated to be right-hand dominant: Holder, M.K. (1997), Why are more people right-handed?. Sciam.com, Scientific American Inc.

[21] Such meanings are found also in expressions like to have two left thumbs or in German zwei linke Hände (haben) that carry meanings like ‘clumsy fellow’, ‘awkward’, ‘uncoordinated’, ‘ungainly’, ‘graceless’, ‘inelegant’, ‘inept’, ‘maladroit’, ‘unskilful’. This derived sense is also found in cognate Middle Dutch and Low German luchter, luft. Compare Lithuanian kairys ‘left’ and Lettish kreilis ‘left hand’ both from a root that yields words for ‘twisted, crooked’. [Online Etymology Dictionary], accessed 26.7.2017, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=left

[22] Compare East Frisian luf, Dutch dialectal loof ‘weak, worthless’.

[23] The usual Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root *dek- is represented by Latin dexter (also dexterity). Other derivations on a similar pattern to English right are French droit, from Latin directus ‘straight’, Lithuanian labas, literally ‘good’ and Slavic words (Bohemian pravy, Polish prawy, Russian pravyj) from Old Church Slavonic pravu, literally ‘straight’ from PIE *pro-, from root *per- ‘forward’ hence ‘in front of, before, first, chief. [Online etymology dictionary], accessed 23.6.2017, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=right

[24] Council of Constantinople, Creed of Constantinople 381 a. Chr.: “he was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered, and was buried, and the third day he rose again, according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of the Father”.

[25] “Since, then, you have been raised with Christ, set your hearts on things above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of God.” Colossians 3:1. The Bible. The New Oxford Annotated Version, 3rd ed., Oxford UP, 2001. In terms of work ethics, Christians were historically commanded to put in their best efforts in whatever they do to “work at it with all [their] heart” as they are always subject to reward by the Lord. Colossians 3:25–25, ibid.

[26] The original meaning of responsible came from the Latin stem respons-. The verb respond goes back to the 12th century’s respound carrying the meaning ‘respond, answer to, promise in return,’ from re- ‘back’ + spondere ‘to pledge’. Respons- is past participle stem of verb respondere ‘to respond’. Spondee means ‘solemn libation, a drink-offering’ and denotes the ‘metrical foot consisting of two long syllables’ originally from Greek spondeios (pous) the name of the meter originally used in chants accompanying libations. The verb spendein ‘make a drink offering’ from PIE root *spend- ‘to make an offering, perform a rite’ hence ‘to engage oneself by a ritual act’, which were seen as an act for forgiveness in front of the divine judgment. [Online etymology dictionary], accessed 23.6.2017, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=respond&allowed_in_frame=0

[27] From Sanskrit *raj- ‘a king, a leader’ in many Indo-European languages we observe similar development: i.e. Latin regere ‘to rule, direct, lead, govern’, rex (genitive regis) ‘king’, rectus ‘right, correct’, Greek oregein ‘to reach, extend’, Old Irish ri, Gaelic righ ‘a king’, Gaulish -rix ‘a king’ (i.e. VircingetoRIX), Old Irish rigim ‘to stretch out’, Gothic reiks ‘a leader’; Old English rice ‘kingdom’ -ric ‘king’ rice ‘rich, powerful’ riht ‘correct’, Gothic raihts, Old High German recht, Old Swedish reht, Old Norse rettr ‘correct’. Online Etymology Dictionary: right, *h3reg- *deks-. [Online etymology dictionary], accessed 15.6.2017 http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=right

[28] Binary oppositions are pairs of related terms or concepts that are opposite in meaning. They form the system in language and thought by which two theoretical opposites are defined and set off against one another.

[29] Carroll, A.B. (1979), p. 500.

[30] Some companies follow the assumption of CSR as a communication strategy due to the external need to manage stakeholders’ image and reputation. Stachowicz-Stanusch, A., Mangia, G., Caldarelli, A. and Amann, W. (2017), p. 147.

[31] Stachowicz-Stanusch et al. (2017), pp. 103–104.

[32] In the past decade, the problems and failure of economic rationality to account for the realities have prompted economists to search for more robust formulations that consider morality and socially conscious behaviours through the use of game theory. See, e.g. Samuelson, L. (2002). “Evolution and Game Theory”. Journal of Economic Perspectives 16(2): 47–66. Prior to game theory, consideration of moral codes in economics was internationally well-known through the work of an Indian economist and philosopher, Amartya Sen. e.g. Sen, A.K. (1982). Choice, Welfare, and Measurement. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

[33] Amao, O. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility, Human Rights and the Law: Multinational Corporations in Developing Countries, Taylor & Francis, p. 83.

[34] The social contract concept, as originally developed by Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau, is seriously discussed in the context of corporate social responsibilities. See, e.g. Dahl, R.A. (1972). ‘A Prelude to Corporate Reform’. Business & Society Review, Spring issue, pp. 17-23; Amao, O. (2011), pp. 106–109.

[35] Matten, D. and Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166–179; Altman, B.W. and Vidaver-Cohen, D. (2002). A framework for understanding corporate citizenship: Introduction to the special edition of Business and Society Review “Corporate Citizenship for the New Millennium”. Business and Society Review, 105(1), 1–7.

[36] The homo economicus archetype was first conceived in 1836 by John Stuart Mill, who saw an economic man as “…solely as a being who desires to possess wealth, and who is capable of judging the comparative efficacy of means for obtaining that end”. Mill, John Stuart. (1836). ‘On the definition of political economy and the method of investigation proper to it.’ Reprint in 1967, Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, 4, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, p. 321. It should be noted that for Mill, the meaning of wealth is not only about material pleasures but also other pursuits such as leisure, luxury and procreation.

[37] e.g. Cohen, D. (2014). Homo Economicus: The (Lost) Prophet of Modern Times. John Wiley & Sons.

[38] Robbins, L. (1945). An Essay On The Nature And Significance Of Economic Science. London: Macmillan and Co. Limited, p. 16.

[39] Adam Smith (1776) suggested that humans can unintentionally promote public interests by acting on their own self-interest. This narrative underpins mainstream economic theories. In Microeconomics: e.g. von Neumann, J. and Morgenstern, O., (1944). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, Princeton University Press; Arrow, K. and Debreu, G. (1954). Existence of an Equilibrium for a Competitive Economy, in Econometrica, 22:3, 265–290. In Macroeconomics: e.g. Walras, L. (1877). Éléments d’économie politique pure, ou théorie de la richesse sociale, L. Corbaz, Lausanne; Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of Economics, Macmillan and Co.; Keynes, J.M. (1936). The general theory of interest, employment and money, Macmillan Cambridge University Press; Lucas, R. and Sargent, T. (1979). After Keynesian Macroeconomics, in: Quarterly Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 3(2); Mankiw, N. and Romer, D. (1991). New Keynesian Economics: Coordination failures and real rigidities (Vol. 2), The MIT Press.

[40] Economists substitute for “utility” another term such as “self-interest”, or “well-being”. Samuelson, P.A. (1948). Economics, an Introductory Analysis. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

[41] Etzioni, A. (2011). ‘Behavioral Economics: Toward a New Paradigm’, American Behavioral Scientist, 55 (8), 1099–1119, p. 1108; Frey, B.S. and Stutzer, A. (2007). ‘Economics and Psychology: Developments and Issues’ in Frey, B. and Stutzer, A. (eds.). Economics and Psychology: A Promising New Cross-Disciplinary Field. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 3.

[42] The term “commons” connects the elements of the natural and the social or cultural world. As an alternative basis for the law of nature, it is not based on deterministic ideas of optimisation and growth, but “an intricate understanding of embodied freedom and its relationship to the whole”. Hardin, G. (1968). ‘The Tragedy of the Commons,’ Science, 162, 1243–1248. See also Weber, A. (2012). ‘The Economy of Wastefulness: The Biology of the Commons’ in Bollier, D. and Helfrich, S. (eds.), The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State (Levellers Press, 2012), part I.

[43] Modern behavioural economists acknowledge some relations between economic behaviour and ethical considerations. See Dixon, W. and Wilson, D. (2013). A History of Homo Economicus: The Nature of the Moral in Economic Theory, Routledge.

[44] Howie, L. and Campbell, P. (2017). Crisis and Terror in the Age of Anxiety: 9/11, the Global Financial Crisis and ISIS, Springer; also Bauman, Z. (2013).

[45] Illich, I. (1973). Tools for Conviviality. New York, Harper and Row; (1973). Energy and Equity. Calder & Boyars; (1971). Deschooling Society. New York, Harper and Row. Illich’s social critique was developed primarily in response to international development efforts when Illich was serving as a Catholic priest in Mexico. See also essays in Bollier, D. and Helfrich, S. (eds.) (2012). The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State. Levellers Press.

[46] Illich, I. (1973). Energy and Equity. Calder & Boyars.

[47] Chomsky, N. (1970). Language and Freedom. Lecture at the University Freedom and the Human Sciences Symposium, Loyola University, Chicago, 8–9 January 1970. Published with permission from Peck, J. (ed.) (1987). The Chomsky Reader, in: Chomsky.info, accessed 25.07.2017.

[48] The basis of Humboldt’s social and political thought is his vision “of the end of man” as “the highest and most harmonious development of his powers to a complete and consistent whole”. For Humboldt, “Sounds do not become words until a meaning has been put into them, and this meaning embodies the thought of a community”. The Heterogeneity of Language and Its Influence on the Intellectual Development of Mankind’ in Weissbach, M.M. (1999). Wilhelm von Humboldt’s Study of the Kawi Language: The Proof of the Existence of the Malayan-Polynesian Language Culture, Fidelio Magazine VIII (1).

[49] Chomsky, N. (1970), p. 93; Chomsky, Language and Problems of Knowledge, 1988 in: the Managua Lectures, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, p. 155); Chomsky, N. (1979). Reflections on Language, p. 6.

[50] Von Humboldt, W. (1836). On Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[51] “The quest for better explanations may well indeed be infinite, but infinite is of course not the same as limitless. English is infinite, but doesn’t include Greek. The integers are an infinite set, but do not include the reals […].” Chomsky, N. (2014). Science, Mind, and Limits of Understanding in: Foundation (STOQ), The Vatican, January, in: Chomsky.info accessed 27.07.2017.

[52] Relevant to our arguments, it should be noted here that Chomsky’s rationalist conception of human nature provides the basis for a “nontrivial” theory of human nature. Nonetheless, his theory proposes a sound empirical hypothesis about human faculty of language which gives no room for superficial preconceptions or a priori dogma and will be subject to debates in behavioural sciences and empirical confirmation. Otero, C.P. (1994). Noam Chomsky: Critical Assessments, Volumes 2–3, Taylor & Francis, pp. 279, 289.

[53] Rousseau, J.J. Discourses on Inequality in: Chomsky, N. (1970), pp. 90–93.

[54] Chomsky, N. (2008), p. 89.

[55] Illich, I. (1973). Tools for Conviviality.

[56] Weber, A. (2012), part I.

[57] Amao, O. (2011), p. 106, who discussed the theory of social contract and argued from the legal standpoint based on the jurisprudence of corporations being similar to a natural person (pp. 98–106).

[58] Granovetter, M. (1985), Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness, in: American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 91, No. 3 (Nov.), pp. 481–510. His approach to embeddedness diverges from the formalist and substantivist thinking of the market which he criticised both as under- and over-exaggerating the role of human and social relations. On the one hand, the formalist approach to the market is critiqued for taking too little account of socialised aspects of human action as social relations are treated as impediments to competitive markets (pp. 483, 484). On the other, the substantivist approach in economic embeddedness also misrepresents “social influences” as “processes in which actors acquire customs, habits, or norms that are followed mechanically and automatically, irrespective of their bearing on rational choice”. (p. 485) Substantivist embeddedness in anthropology is often associated with Karl Polanyi and the idea of “moral economy” in history and political science. Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. New York: Farrar and Rinehart.

[59] Granovetter, M. (1985), pp. 482, 485.

[60] Granovetter, M. (1985), p. 490.

[61] Granovetter, M. (1985), p. 487.

[62] When we think of norms and institutions, it is important to make distinction between the two. Norms “are mental representations stored in individual brains that got there through some form of learning” and “could be composed of a combination of preferences and beliefs, mental models (or scripts and schema) and motivations or decision rules and expectations.” Institutions are thought of as established collective values and practices distilled from actors’ interactions, decisions and learning process. Institutions can be formal such as those established and reinforced by written laws, policies and sanction mechanisms. At the level of individual and localised norms and beliefs, institutions can also be informal – which by definition do not necessarily conform to logical reasoning and prescription provided by formal institutions. See in Ensminger, J. and Henrich, J. (2014). Experimenting with Social Norms: Fairness and Punishment in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Russell Sage Foundation, p. 20.

[63] Ruggie, J. (2008). Protect, Respect and Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. UN Doc A/HRC/8/5, para 2.

[64] Ruggie, J. (2008), para 7.

[65] The most important document is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (General Assembly resolution 217 A). The UDHR is a cornerstone document in the history of human rights, sets out fundamental human rights to be universally protected and was proclaimed as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It was drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world and has so far been translated into over 500 languages. For the drafting history and discussions on the role of freedom and equality in the Declaration prior to its adoption in Morsink, J. (1999). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting, and Intent. University of Pennsylvania Press. See also Amnesty International, (2011). Freedom: Short Stories Celebrating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Random House.

[66] Amao, O. (2011), p. 106.

[67] See the Preamble and Arts 1, 2 and 55 of the UN Charter.

[68] Ruggie, J. (2008). Protect, Respect and Remedy Framework. UN Doc A/HRC/8/5, para 8.

[69] Bottomley, S. (2002), ‘Corporations and Human Rights’ in Bottomley, S. and Kinley, D. (eds.), Commercial Law and Human Rights, Aldershot, Ashgate, p. 47.

[70] See Horrigan, B. (2010), Chapter 9.

[71] These refer to, among others, Draft UN Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights, UN Resolution 2003/16.2; Voluntary, Ethical Codes of Conduct (VCCs). Horrigan, B. (2010), p. 302.

[72] See, e.g. Ruggie, J. (2008). Protect, Respect and Remedy Framework. UN Doc A/HRC/8/5; UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011).

[73] Horrigan, B. (2010), p. 320.

[74] In March 2017, FIFA announced its establishment of an independent Human Rights Advisory Board to help strengthen its efforts to ensure respect for human rights. The Board comprises international experts in human – including labour – rights and anti-corruption issues from the United Nations, trade unions, civil society and business. The Board provides FIFA with advice on all issues that it considers relevant to the implementation of FIFA’s human rights responsibilities under Article 3 of the FIFA Statutes. This development came as a result of the published independent report by Professor John Ruggie in April 2016. See, Ruggie, J. (2016), “For the Game. For the World”. Shift Project/Harvard Kennedy School.

[75] e.g. ABB applied human rights considerations in its supply chain investigation and found two suppliers involved in child labour. They immediately introduced corrective measures. ABB Group. (2011). Sustainability Performance. Zurich, ABB.

[76] e.g. Intrust Global’s INDI Fund partners with indigenous and rural communities in Latin America to package projects for investors. It features a unique private equity model that gives poor indigenous communities in Latin America an equity stake in projects in exchange for use/contribution of their land and natural resources. It has been referred to as successful ‘ethical funds’ for the human rights of indigenous peoples in Latin America. Ayoubi, T. and Acuna, F. (2010). Sustainable Equity Fund Investments within Latin America – Case of Indigenous People, School of Management Blekinge Institute of Technology.

[77] International Labour Organization (ILO) and International Organisation of Employers (IOE), (2015). How to do business with respect for children’s right to be free from child labour: ILO-IOE child labour guidance tool for business. ILO, Geneva.

[78] John Ruggie speaking as Shift Chair and workshop participant in Shift, (2012). Embedding Respect for Human Rights Within a Company’s Operations. Workshop Report No. 1, p. 2.

[79] United Nations (2011). UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. UN Doc. HR/PUB/11/04.

[80] The Taisei Group has integrated human rights in its overall principles of conduct, CSR and core structure of values to implement the company’s philosophy as well as the corporation KPI. The company has developed its Human Rights Policy with reference to international human rights standards such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the eight fundamental conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the ISO 26000. The company also incorporated international labour standards on prohibiting child labour, compulsory labour and discrimination in employment and occupation and on guaranteeing the right of association and the right to bargain collectively. The respect for human rights is also a requirement in its supply chain and procurement activities. Taisei Group, (2016). Annual Report, pp. 41–43, 54, 65. Accessed 6.11.2017 at http://www.taisei.co.jp/english/ir/image/ar2016/taisei_annual_2016_all.pdf

[81] See further discussions and examples in Shift, (2012). Embedding Respect for Human Rights Within a Company’s Operations. Workshop Report No. 1, pp. 3–4.

[82] According to lessons learned from different companies that participated in a Shift workshop, the question of how to organise the human rights function and where to locate it is very much context-dependent. Shift, (2012). Embedding Respect for Human Rights Within a Company’s Operations. Workshop Report No. 1, p. 7.

[83] African good practices: Tesco’s fruit supply chain in South Africa has farm-level labour grievance mechanisms which included recourse to a government labour relations body, namely the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA), when the farm-level mechanism was unable to provide a resolution. In Ghana, Newmont’s community grievance mechanisms include a recourse to the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), the national human rights institute of Ghana, as well as community-level committees for dealing with certain sub-sets of issues. See Shift, (2014). Remediation, Grievance Mechanisms, and the Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights. Shift Workshop Report No. 5. New York, pp. 6, 17.

[84] Shift, (2012). Embedding Respect for Human Rights Within a Company’s Operations. Workshop Report No. 1, p. 11.

[85] The International Bill of Human Rights refers to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) with its two Optional Protocols and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966). Available at http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Compilation1.1en.pdf, accessed 21.09.2017.

[86] Adopted by the International Labour Conference at its eighty-sixth session, Geneva, 18 June 1998. The Declaration commits Member States to respect and promote principles and rights in four categories, whether or not they have ratified the relevant labour conventions. Available at http://www.ilo.org/declaration/info/publications/WCMS_467653/lang--en/index.htm, accessed 21.09.2017.

References

Aasland, D.G. (2004). On the Ethics Behind “Business Ethics”, in: Journal of Business Ethics, August, Volume 53, Issue 1, pp. 3–8.

Altman, B.W. and Vidaver-Cohen, D. (2002). A framework for understanding corporate citizenship: Introduction to the special edition of Business and Society Review “corporate citizenship for the new millennium”, in: Business and Society Review, 105(1), pp. 1–7.

Amao, O. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility, Human Rights and the Law: Multinational Corporations in Developing Countries. Taylor & Francis.

Amnesty International (2011). Freedom: Short Stories Celebrating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Random House.

Arrow, K. and Debreu, G. (1954). Existence of an Equilibrium for a Competitive Economy, in: Econometrica, 22:3, 265–290.

Avalos, G. (2015). Poverty rates near record levels in Bay Area despite hot economy, San Jose Mercury News, 1 April 2015, available at http://www.mercurynews.com/business/ci_27830698/poverty-rates-near-record-levels-bay-area-despite, accessed on 20.10.2017.

Ayoubi, T. and Acuna, F. (2010) Sustainable Equity Fund Investments within Latin America – Case of Indigenous People. Thesis for the Master’s degree in Business Administration, MBA programme Fall/Spring 2010. School of Management Blekinge Institute of Technology.

Bauman, Z. (2013). Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity.

Bollier, D. and Helfrich, S. (eds.) (2012). The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State. Levellers Press.

Bowen, H.R. (1953). Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. Harper & Row, New York.

Carroll, A.B. (1991). The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders, in: Business Horizons, 34: 39–48.

________ (1979). A three dimensional model of corporate social performance, in: Academy of Management Review, 4, pp. 497–505.

Chomsky, N. (2014). Science, Mind, and Limits of Understanding, in: Foundation (STOQ), The Vatican, January 2014, in: Chomsky.info

________ (2008). The Essential Chomsky, Penguin Books.

________ (1988). Language and Problems of Knowledge, in: the Managua Lectures. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

________ (1979). Reflections on Language. Fontana.

________ (1970). Language and Freedom. Lecture at the University Freedom and the Human Sciences Symposium, Loyola University, Chicago, January 8–9, 1970. Published with permission from Peck, J. (ed.) (1987). The Chomsky Reader, in: Chomsky.info, accessed 25.07.2017.

Cohen, D. (2014). Homo Economicus: The (Lost) Prophet of Modern Times. John Wiley & Sons.

Council of Constantinople, (381). Creed of Constantinople 381 a. Chr.

Dahl, R.A. (1972). A Prelude to Corporate Reform, in: Business & Society Review, Spring issue.

Dixon, W. and Wilson, D. (2013). A History of Homo Economicus: The Nature of the Moral in Economic Theory. Routledge.

Donham, W.B. (1929). Business Ethics – A General Survey, in: Harvard Business Review 7(4):385–94.

Ensminger, J. and Henrich, J. (2014). Experimenting with Social Norms: Fairness and Punishment in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Russell Sage Foundation.

Etzioni, A. (2011). Behavioral Economics: Toward a New Paradigm, in: American Behavioral Scientist, 55 (8), 1099–1119.

Frey, B.S. and Stutzer, A. (2007). Economics and Psychology: Developments and Issues. In Frey and Stutzer (eds.), Economics and Psychology. A Promising New Cross-Disciplinary Field (pp. 3–15). MA: MIT Press, Cambridge.

Granovetter, M. (1985), Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness, in: American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 91, No. 3 (Nov.), pp. 481–510.

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons, in: Science, 162, 1243–1248.

Harris, R. (1988). Language, Saussure and Wittgenstein: How to Play Games with Words. Routledge, London.

Hetherington J.A.C. (1973). Corporate Social Responsibility Audit: A Management Tool for Survival. The Foundation for Business Responsibilities, London.

Holder, M.K. (1997). Why are more people right-handed? in: Sciam.com, Scientific American Inc.

Horrigan, B. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility in the 21st Century: Debates, Models and Practices Across Government, Law and Business. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Howie, L. and Campbell, P. (2017). Crisis and Terror in the Age of Anxiety: 9/11, the Global Financial Crisis and ISIS. Springer.

Von Humboldt, W. (1836/1988). On Language. Texts in German Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. Translated from the German by Peter Heath.

Illich, I. (1973). Tools for Conviviality. Harper and Row, New York.

________ (1973). Energy and Equity. Calder & Boyars.

________ (1971). Deschooling Society. Harper and Row, New York.

ILO/IOE. (2015). How to do business with respect for children’s right to be free from child labour. ILO-IOE child labour guidance tool for business. ILO, Geneva.

Iverson, G.K. and Salmons, J.C. (1992). The phonology of the Proto-Indo-European root structure constraints, in: Lingua, Issue 4, Vol. 87, August 1992, pp. 293–320.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of interest, employment and money. Macmillan Cambridge University Press.

Kristoffersen, I., Gerrans, P. and Clark-Murphy, M. (2005). The Corporate Social Responsibility and the Theory of the Firm. School of Accounting, Finance, and Economics, FIMARC Working Paper Series No. 0505. Edith Cowan University.

Laasch, O. and Conaway, R.N. (2014). Principles of Responsible Management: Global Sustainability, Responsibility, and Ethics. Cengage Learning, pp. 114–115.

Lewis, V.P. (1985). Defining ‘Business Ethics’: Like Nailing Jello to a Wall, in: Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 4, No. 5 (Oct), pp. 377–383.

Lucas, R. and Sargent, T. (1979). After Keynesian Macroeconomics, in: Quarterly Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 3(2).

Mankiw, N. and Romer, D. (1991). New Keynesian Economics: Coordination Failures and Real Rigidities (Vol. 2). The MIT Press.

Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of Economics. Macmillan and Co.

Matten, D. and Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization, in: Academy of Management Review, 30(1), pp. 166–179.

Mill, J.S. (1836). On the definition of political economy and the method of investigation proper to it, Reprint in 1967, Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, 4, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Moon, J. (2014). Corporate Social Responsibility: A Very Short Introduction. OUP, Oxford.

Morsink, J. (1999). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting, and Intent. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Online Etymology Dictionary. https://www.etymonline.com/ accessed 26.7.2017.

Otero, C.P., (1994). Noam Chomsky: Critical Assessments, Volumes 2–3. Taylor & Francis.

Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Farrar and Rinehart, New York.

Roberts, J. (2001). Corporate Governance and the Ethics of Narcissus, in: Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Jan., 2001), pp. 109–127.

Robbins, L. (1945). An Essay On The Nature And Significance Of Economic Science. Macmillan and Co. Limited, London.

Rousseau, J.-J. (2003). A Discourse on Inequality. Penguin UK.

Ruggie, J. (2016). For the Game. For the World. Shift Project/Harvard Kennedy School.

________ (2008). Protect, Respect and Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights. Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. UN Doc A/HRC/8/5.

Samuelson, L. (2002). Evolution and Game Theory, in: Journal of Economic Perspectives 16(2): 47–66.

Samuelson, P.A. (1948). Economics: An Introductory Analysis. McGraw-Hill Inc. US.

Schwab, K. (2017). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Penguin UK.

Sen, A.K. (1982). Choice, Welfare and Measurement. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Shift, (2014). Remediation, Grievance Mechanisms, and the Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights. Shift Workshop Report No. 5. Shift, New York.

_____(2012). Embedding Respect for Human Rights Within a Company’s Operations. Shift Workshop Report No. 1. Shift, New York.

Smith, A. (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Strahan and Cadell, London.

Stachowicz-Stanusch, A., Mangia, G., Caldarelli, A. and Amann, W. (2017). Organizational Social Irresponsibility: Tools and Theoretical Insights. Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, NC.

Stachowicz-Stanusch, A., Amann, W. and Mangia, G. (2017). Corporate Social Irresponsibility: Individual Behaviors and Organizational Practices. Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, NC.

Stachowicz-Stanusch, A., (2016). Corporate Social Performance: Reflecting on the Past and Investing in the Future. Information Age Publishing, Charlotte, NC.

Taisei Group, (2016). Annual Report. Available at http://www.taisei.co.jp/english/ir/image/ar2016/taisei_annual_2016_all.pdf. Accessed on 6.11.2017.

Visser, W. and Tolhurst, N. (2010). The World Guide to CSR: A Country-by-Country Analysis of Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility. Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield.

von Neumann, J. and Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton University Press.

Walras, L. (1877). Éléments d’économie politique pure, ou théorie de la richesse sociale, L. Corbaz, Lausanne.

Weber, A. (2012). The Economy of Wastefulness: The Biology of the Commons, in: Bollier, D. and Helfrich, S., (eds.) The Wealth of the Commons: A World Beyond Market and State. Levellers Press.

Weissbach, M.M. (1999). Wilhelm von Humboldt’s Study of the Kawi Language: The Proof of the Existence Of the Malayan-Polynesian Language Culture, in: Fidelio Magazine. VIII (1).